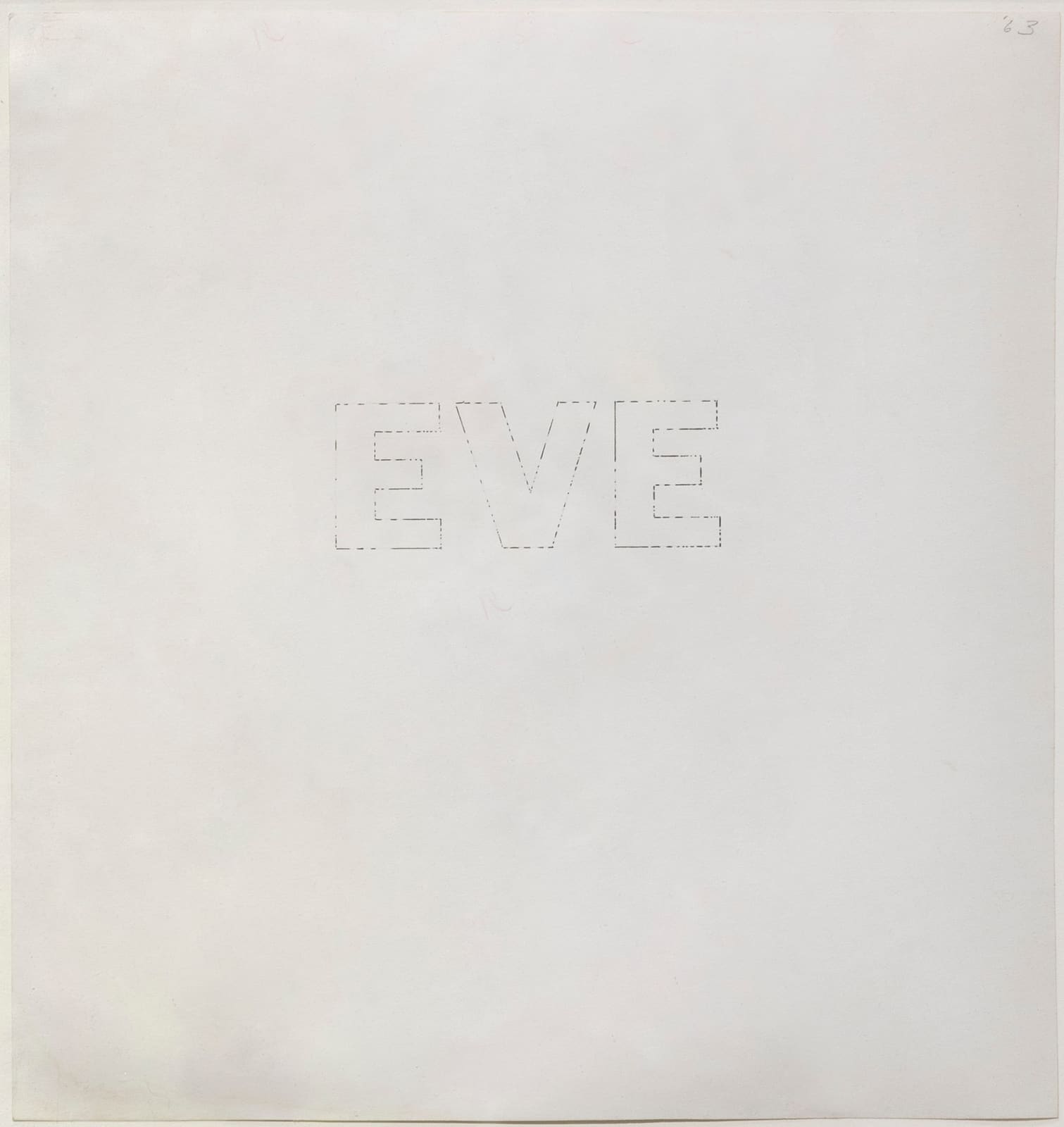

Ed Ruscha

Eve, 1963

Ink and pencil on paper

27 x 25.4 cm. (10 5/8 x 10 in.)

Further images

Ed Ruscha’s Eve, 1963, is a rare and important work as well as an object of both conceptual and personal significance, its surface registering the artist’s preoccupation with language as...

Ed Ruscha’s Eve, 1963, is a rare and important work as well as an object of both conceptual and personal significance, its surface registering the artist’s preoccupation with language as form, sign, and affect. Inscribed to Eve Babitz, muse, writer, and one of the central figures of Los Angeles’ cultural milieu, the work operates at the intersection of image and text, where word becomes both utterance and material. That Eve is signed by Ruscha – a rarity in his practice – only amplifies its singular status, marking it as an intimate artefact within his oeuvre, a work not merely of linguistic play but of devotion.

Here, in Eve, we encounter language as both pictorial object and conceptual riddle. The name itself, a palindrome, extends across time in self-reflexive mirroring – its presence, doubled, its meaning at once concrete and elusive. Ruscha’s fascination with the fluidity of the American vernacular finds itself distilled in these three letters: a word both ordinary and mythic, one that oscillates between the biblical and the banal, between woman and idea.

Ruscha himself recalled the work in an interview with a kind of wistful ambiguity. When asked about the work, he replied: “I did [draw her] with really soft lines. Very faint. I don’t know whatever happened to that.” The description is almost spectral, as though the name – Eve – exists on the brink of disappearance, a whisper of graphite on paper, dissolving into the very medium of its creation. But this faintness is precisely the point: Ruscha’s engagement with language often renders words unstable, transient, suspended between presence and erasure.

Babitz, too, was no mere recipient but an active participant in the cultural fabric of Los Angeles, her presence entwined with Ruscha’s own aesthetic sensibilities. As the 1982 edition of L.A. Woman proclaimed, “Eve Babitz holds the primal knowledge of what it is to be a woman in what she convinces us is the capital of civilization.” In Eve, 1963, this primal knowledge is inscribed not in narrative but in form, in the ineffable pull of a name reduced to its essential structure.

Here, in Eve, we encounter language as both pictorial object and conceptual riddle. The name itself, a palindrome, extends across time in self-reflexive mirroring – its presence, doubled, its meaning at once concrete and elusive. Ruscha’s fascination with the fluidity of the American vernacular finds itself distilled in these three letters: a word both ordinary and mythic, one that oscillates between the biblical and the banal, between woman and idea.

Ruscha himself recalled the work in an interview with a kind of wistful ambiguity. When asked about the work, he replied: “I did [draw her] with really soft lines. Very faint. I don’t know whatever happened to that.” The description is almost spectral, as though the name – Eve – exists on the brink of disappearance, a whisper of graphite on paper, dissolving into the very medium of its creation. But this faintness is precisely the point: Ruscha’s engagement with language often renders words unstable, transient, suspended between presence and erasure.

Babitz, too, was no mere recipient but an active participant in the cultural fabric of Los Angeles, her presence entwined with Ruscha’s own aesthetic sensibilities. As the 1982 edition of L.A. Woman proclaimed, “Eve Babitz holds the primal knowledge of what it is to be a woman in what she convinces us is the capital of civilization.” In Eve, 1963, this primal knowledge is inscribed not in narrative but in form, in the ineffable pull of a name reduced to its essential structure.