Rebecca Ness American , b. 1992

Altar, 2025

Oil on linen

177.8 x 228.6 cm. (70 x 90 in.)

Copyright The Artist

Further images

Although Rebecca Ness does not paint herself directly in Altar (2025), she is everywhere in it. The painting gathers a spill of belongings on her windowsill and bedroom floor caught...

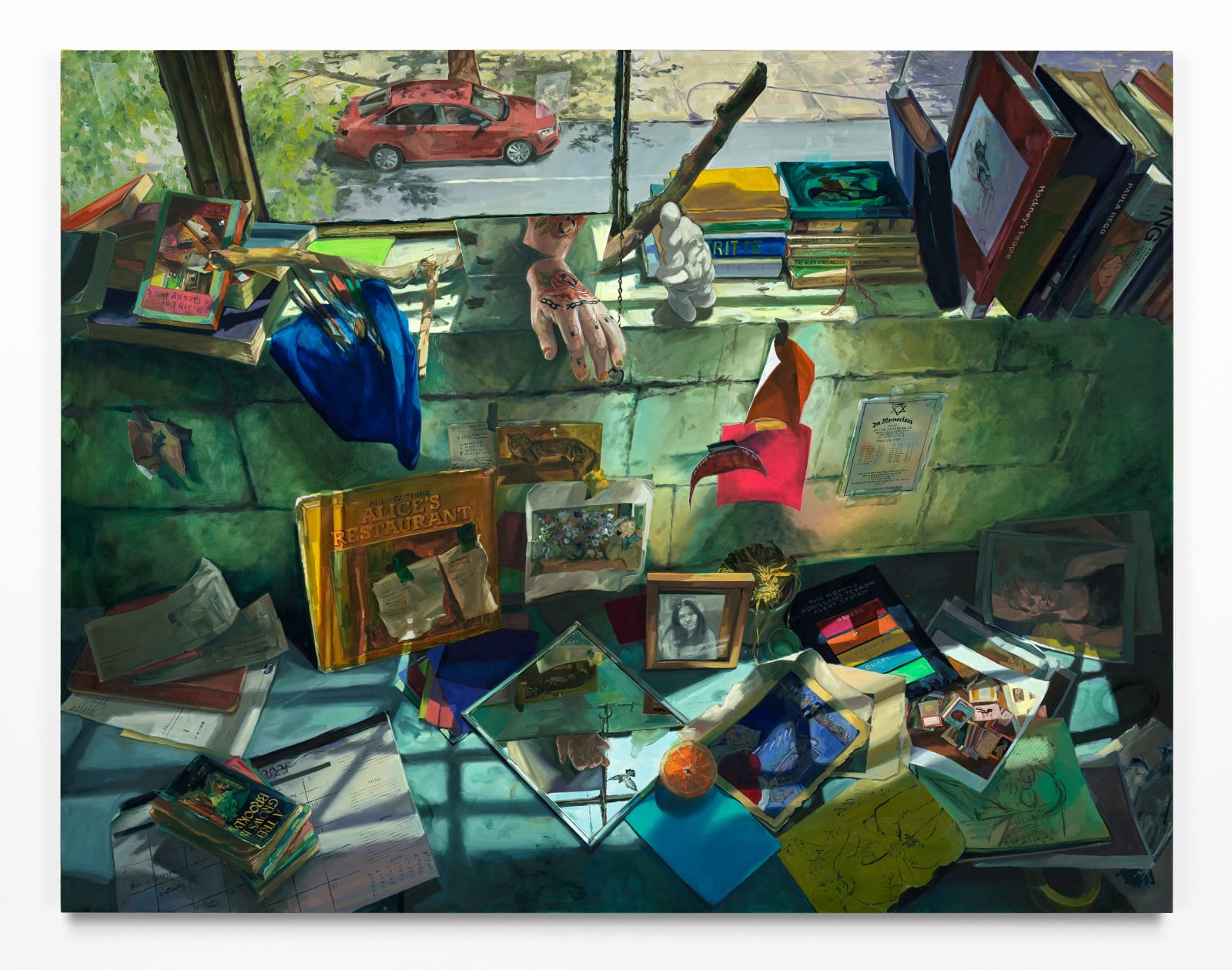

Although Rebecca Ness does not paint herself directly in Altar (2025), she is everywhere in it. The painting gathers a spill of belongings on her windowsill and bedroom floor caught in a shaft of sunlight. Conspicuously present through her things, she invites us to read backwards from objects to life, piecing together a narrative from traces. It unfolds less like a still life than like an archaeological site of self.

Altar is a portrait of grief, stitched from fragments the artist has chosen, or been forced, to hold. At its centre sits a black-and-white photograph of Ness’s mother, whose recent death shadows the series and lends the title its religious charge. Through the window a red car waits, a parking ticket pinned to its windscreen – a small but telling emblem of mourning’s inertia, when even the most ordinary obligations slide into neglect. The domestic scene takes on the gravity of ritual space, reconfiguring everyday clutter into votive offering.

Altars and altarpieces have long served as conduits for transcendence, from Duccio’s Maestà to Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece. Ness relocates this sacred form into the realm of the intimate, transfiguring the quotidian – records, books, piles of detritus – into vessels of testimony. In this she extends her wider practice, which privileges the banal as carriers of meaning, aligning more with the reliquary than the heroic monument.

Though the composition looks casual, even haphazard, it is exacting: a visual autobiography in which selfhood is displaced into possessions, insisting that the ordinary, scrutinised with care, is where life and memory endure.

Altar is a portrait of grief, stitched from fragments the artist has chosen, or been forced, to hold. At its centre sits a black-and-white photograph of Ness’s mother, whose recent death shadows the series and lends the title its religious charge. Through the window a red car waits, a parking ticket pinned to its windscreen – a small but telling emblem of mourning’s inertia, when even the most ordinary obligations slide into neglect. The domestic scene takes on the gravity of ritual space, reconfiguring everyday clutter into votive offering.

Altars and altarpieces have long served as conduits for transcendence, from Duccio’s Maestà to Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece. Ness relocates this sacred form into the realm of the intimate, transfiguring the quotidian – records, books, piles of detritus – into vessels of testimony. In this she extends her wider practice, which privileges the banal as carriers of meaning, aligning more with the reliquary than the heroic monument.

Though the composition looks casual, even haphazard, it is exacting: a visual autobiography in which selfhood is displaced into possessions, insisting that the ordinary, scrutinised with care, is where life and memory endure.