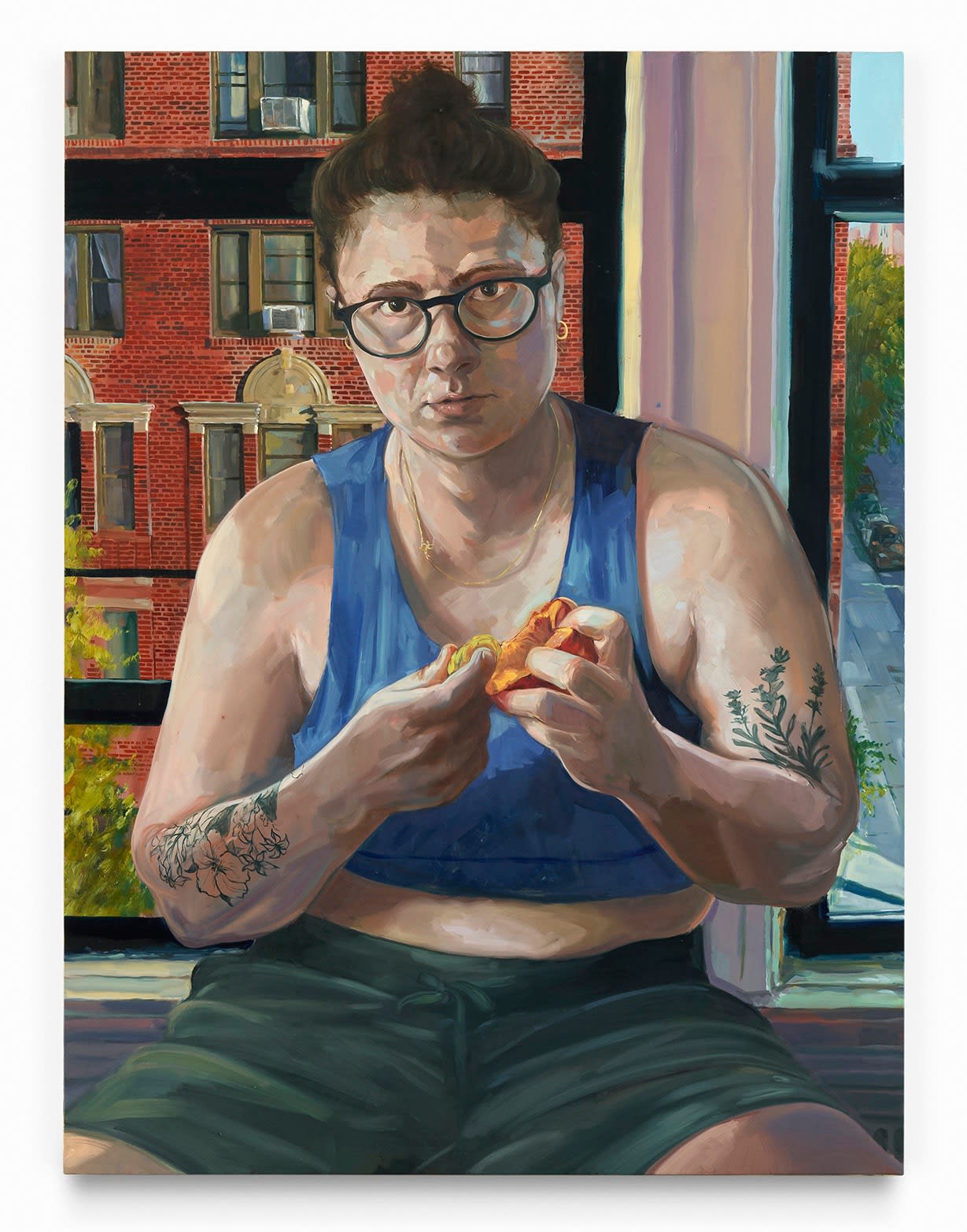

Rebecca Ness American , 1992

Self portrait with a peach, 2025

Oil on linen

101.6 x 76.2 cm. (40 x 30 in.)

Copyright The Artist

Further images

In Self-portrait with a peach (2025), Rebecca Ness paints herself perched on a windowsill, peach in hand, meeting the viewer’s gaze head-on. Behind her, the red brick of New York...

In Self-portrait with a peach (2025), Rebecca Ness paints herself perched on a windowsill, peach in hand, meeting the viewer’s gaze head-on. Behind her, the red brick of New York townhouses rises into a compressed backdrop. The work belongs to a series of self-portraits in which she pairs herself with fruit – the first an homage to Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. Playful, queer, unabashedly tongue-in-cheek, Self-portrait with a peach nods to Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name while weaving in references from artists she reveres.

One of these is Martin Wong, whose tender portraits of his Puerto Rican neighbourhood, particularly La Vida (1988), influenced Ness’s composition. For her, painting New York is a way of fastening herself to place, aligning with artists who made the city both subject and stage. She paints with the specificity of her own neighbourhood, the patch of Brooklyn her family settled in after emigrating from Romania and Poland, inscribing personal and collective histories into the everyday architecture.

Ness’s self-portraits reject the myths of solitary genius and the supposed detachment of the flâneur. She inserts herself instead as participant and witness: a body in flux, embedded in the city’s fabric, alive to its humour, textures and contradictions. By placing herself among them, she folds autobiography into a broader portrait of America and urban life.

One of these is Martin Wong, whose tender portraits of his Puerto Rican neighbourhood, particularly La Vida (1988), influenced Ness’s composition. For her, painting New York is a way of fastening herself to place, aligning with artists who made the city both subject and stage. She paints with the specificity of her own neighbourhood, the patch of Brooklyn her family settled in after emigrating from Romania and Poland, inscribing personal and collective histories into the everyday architecture.

Ness’s self-portraits reject the myths of solitary genius and the supposed detachment of the flâneur. She inserts herself instead as participant and witness: a body in flux, embedded in the city’s fabric, alive to its humour, textures and contradictions. By placing herself among them, she folds autobiography into a broader portrait of America and urban life.