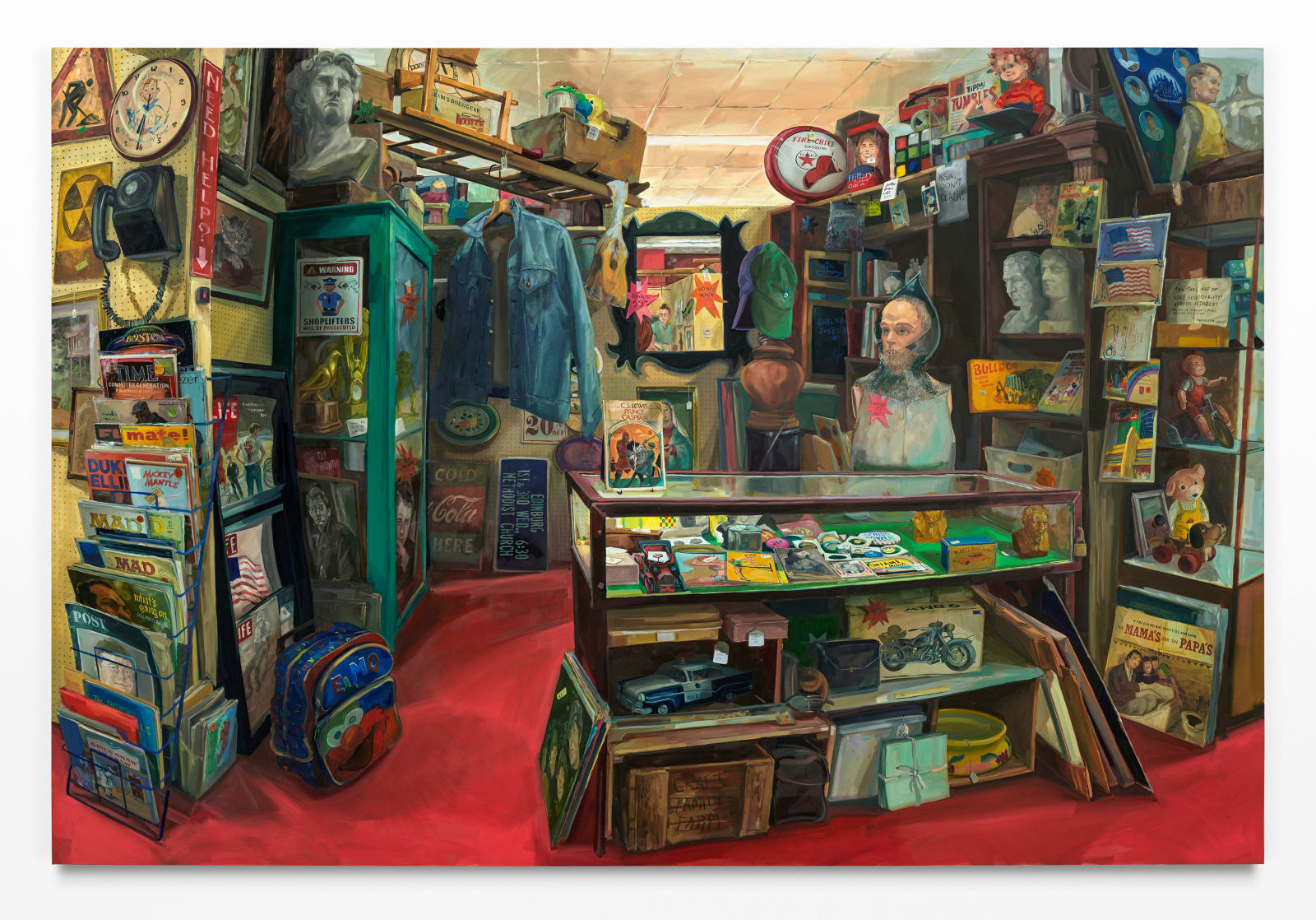

Rebecca Ness American , 1992

Other people's things, 2025

Oil on linen

203.2 x 304.8 cm. (80 x 120 in.)

Copyright The Artist

Further images

In Other people’s things (2025), Rebecca Ness paints a Staten Island thrift shop as both record and excavation: a dense catalogue of objects that doubles as a meta-reflection on painting...

In Other people’s things (2025), Rebecca Ness paints a Staten Island thrift shop as both record and excavation: a dense catalogue of objects that doubles as a meta-reflection on painting itself. Ness inserts herself into the composition via a mirror behind the counter, a clear echo of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, but undercut by a “Do Not Touch” sticker that blocks part of her image. Where van Eyck’s mirror was a guarantee of truth, Ness’s is a reminder of mediation, making a joke of our desire for the “real.” Elsewhere she juxtaposes Michelangelo’s David with a model caricature of Hillary Clinton, collapsing Greenberg’s old distinction between high art and mass culture. The thrift shop becomes a stage where representation itself is shown to be unstable, porous, and political.

Ness calls the painting a “group portrait,” though its subjects are absent: the anonymous owners of the discarded things. In this she touches on Barthes’s punctum – the trace that outlives us, the sting of presence in leftover objects. Her practice, rooted in grief, insists that “we are what we leave behind.” But she also weaves in her own belongings, notably stacks of Life magazines, reorganising debris into a personal cosmology. The thrift shop becomes both documentary and staged, an unreliable narration of reality filtered through her own obsessions.

It is, finally, also a portrait of America, assembled through its cultural detritus: magazines, records, trucker hats, faded signage. In this sense, the work belongs to a lineage that stretches from Pop to postmodernism, probing the cultural unconscious through consumer goods. It is about grief and memory, certainly, but also about how identities are constructed and transmitted through stuff. It is about the mechanics of representation, at once elegy, self-portrait, and sly art-historical commentary. And on another level, it is about painting’s capacity to hold all this – the private, the historical, the absurd, the tragic – in one plane.

Ness calls the painting a “group portrait,” though its subjects are absent: the anonymous owners of the discarded things. In this she touches on Barthes’s punctum – the trace that outlives us, the sting of presence in leftover objects. Her practice, rooted in grief, insists that “we are what we leave behind.” But she also weaves in her own belongings, notably stacks of Life magazines, reorganising debris into a personal cosmology. The thrift shop becomes both documentary and staged, an unreliable narration of reality filtered through her own obsessions.

It is, finally, also a portrait of America, assembled through its cultural detritus: magazines, records, trucker hats, faded signage. In this sense, the work belongs to a lineage that stretches from Pop to postmodernism, probing the cultural unconscious through consumer goods. It is about grief and memory, certainly, but also about how identities are constructed and transmitted through stuff. It is about the mechanics of representation, at once elegy, self-portrait, and sly art-historical commentary. And on another level, it is about painting’s capacity to hold all this – the private, the historical, the absurd, the tragic – in one plane.