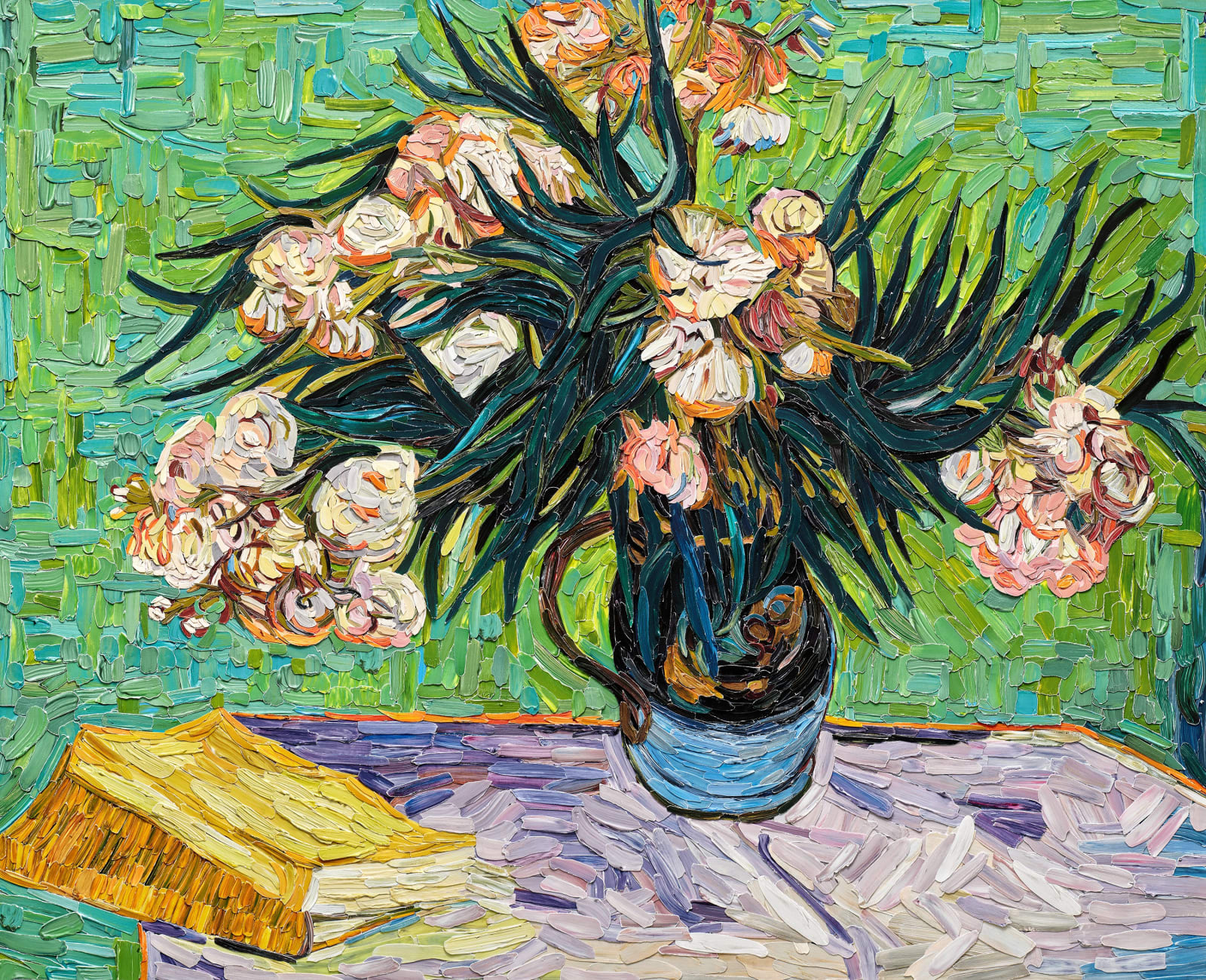

Vik Muniz Brazilian, b. 1961

Oleanders, after Vincent van Gogh (Brushstrokes), 2025

Archival inkjet print

127 x 156.2 cm. (50 x 61 1/2 in.)

Edition of 6 + 4 AP

Copyright The Artist

Further images

Vik Muniz’s Brushstrokes series extends Muniz’s longstanding exploration of visual perception, materiality, and the mechanics of image-making. In Brushstrokes, he turns to the very building block of painting – the...

Vik Muniz’s Brushstrokes series extends Muniz’s longstanding exploration of visual perception, materiality, and the mechanics of image-making. In Brushstrokes, he turns to the very building block of painting – the brushstroke – reconstructing canonical images from the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist traditions through intricately layered photographic collages.

The series draws upon the works of Vincent van Gogh, Joaquín Sorolla, Henri Matisse, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir – painters who, between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, revolutionised pictorial language. Impressionism and its successors rejected academic rigidity in favour of perceptual immediacy, capturing the fugitive effects of light, motion, and atmosphere. These artists did not describe the world through line and contour, but evoked presence through colour – applied in loose, expressive marks that conveyed not exact likeness but lived sensation.

Muniz mines this history, reconstructing their compositions with sculptural swathes of paint – photographed, collaged, and reconstituted into works that oscillate between fidelity and fabrication. Look closely, and each mark is distinct: thick ribbons of ultramarine, ochre, or carmine. Stand back, and the image resolves with startling clarity – a sailboat skimming sunlit water, a still life of fruit, a dappled garden scene. The illusion is complete, yet the means of construction remain nakedly visible.

At first, Muniz assumed that actualising his vision of using brushstrokes to recreate these works would be relatively straightforward. But he soon realised the complexity involved. Each stroke had to be lit with exacting consistency to match the original painting’s directional light. A single inconsistency would collapse the illusion. The process became a puzzle of optics, lighting, and reconstruction – a challenge Muniz embraced. For Muniz, the difficulty is part of the allure. His practice thrives on complexity, and ease rarely holds his interest. Obstacles become catalysts for new ideas, prompting unexpected formal solutions and new conceptual avenues.

The irony is sharp: there are no “real” brushstrokes in these works. What appears gestural is mediated – painted, photographed, digitally sequenced, then reassembled. It’s a hall of mirrors, a play of surfaces and simulacra, but with deep reverence for the innovations of the past. Muniz honours the Impressionists not just by borrowing their imagery, but by drawing attention to the audacity of their vision – how they broke painting down to its essence and built a new reality with nothing more than colour and light.

Painted in Arles in August 1888, Oleanders symbolises vitality and renewal. Van Gogh described the flowers as “always putting out strong new shoots…inexhaustibly.” Their exuberance stands in sharp contrast to the emotional instability the artist was experiencing at the time. The juxtaposition of the oleanders with Émile Zola’s La joie de vivre reflects Van Gogh’s deep engagement with literature and his complex views on life, death, and mental health. He had earlier placed this same book beside a Bible in a still life painted in 1885, suggesting a dialogue between earthly pleasure and spiritual salvation.

The series draws upon the works of Vincent van Gogh, Joaquín Sorolla, Henri Matisse, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir – painters who, between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, revolutionised pictorial language. Impressionism and its successors rejected academic rigidity in favour of perceptual immediacy, capturing the fugitive effects of light, motion, and atmosphere. These artists did not describe the world through line and contour, but evoked presence through colour – applied in loose, expressive marks that conveyed not exact likeness but lived sensation.

Muniz mines this history, reconstructing their compositions with sculptural swathes of paint – photographed, collaged, and reconstituted into works that oscillate between fidelity and fabrication. Look closely, and each mark is distinct: thick ribbons of ultramarine, ochre, or carmine. Stand back, and the image resolves with startling clarity – a sailboat skimming sunlit water, a still life of fruit, a dappled garden scene. The illusion is complete, yet the means of construction remain nakedly visible.

At first, Muniz assumed that actualising his vision of using brushstrokes to recreate these works would be relatively straightforward. But he soon realised the complexity involved. Each stroke had to be lit with exacting consistency to match the original painting’s directional light. A single inconsistency would collapse the illusion. The process became a puzzle of optics, lighting, and reconstruction – a challenge Muniz embraced. For Muniz, the difficulty is part of the allure. His practice thrives on complexity, and ease rarely holds his interest. Obstacles become catalysts for new ideas, prompting unexpected formal solutions and new conceptual avenues.

The irony is sharp: there are no “real” brushstrokes in these works. What appears gestural is mediated – painted, photographed, digitally sequenced, then reassembled. It’s a hall of mirrors, a play of surfaces and simulacra, but with deep reverence for the innovations of the past. Muniz honours the Impressionists not just by borrowing their imagery, but by drawing attention to the audacity of their vision – how they broke painting down to its essence and built a new reality with nothing more than colour and light.

Painted in Arles in August 1888, Oleanders symbolises vitality and renewal. Van Gogh described the flowers as “always putting out strong new shoots…inexhaustibly.” Their exuberance stands in sharp contrast to the emotional instability the artist was experiencing at the time. The juxtaposition of the oleanders with Émile Zola’s La joie de vivre reflects Van Gogh’s deep engagement with literature and his complex views on life, death, and mental health. He had earlier placed this same book beside a Bible in a still life painted in 1885, suggesting a dialogue between earthly pleasure and spiritual salvation.