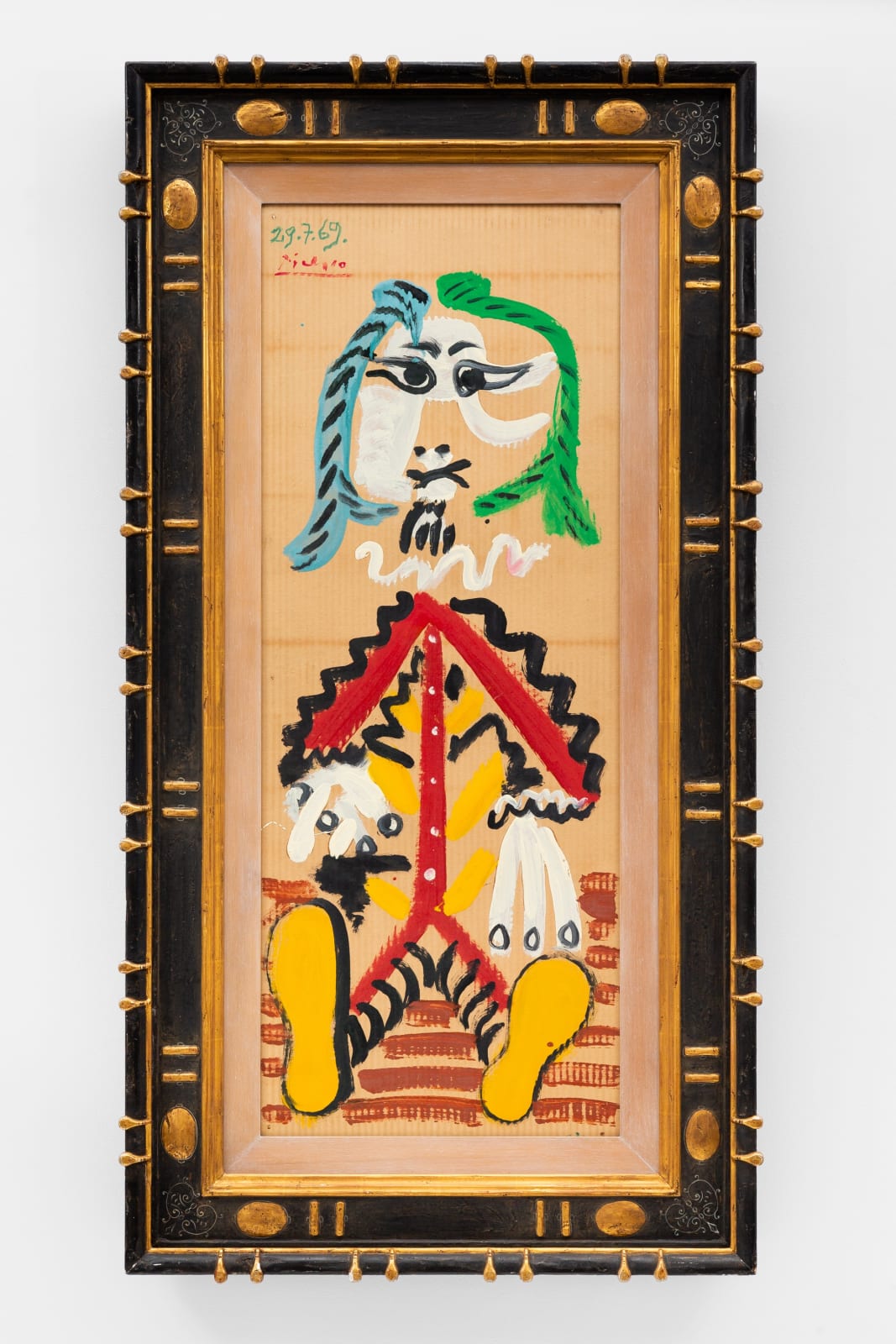

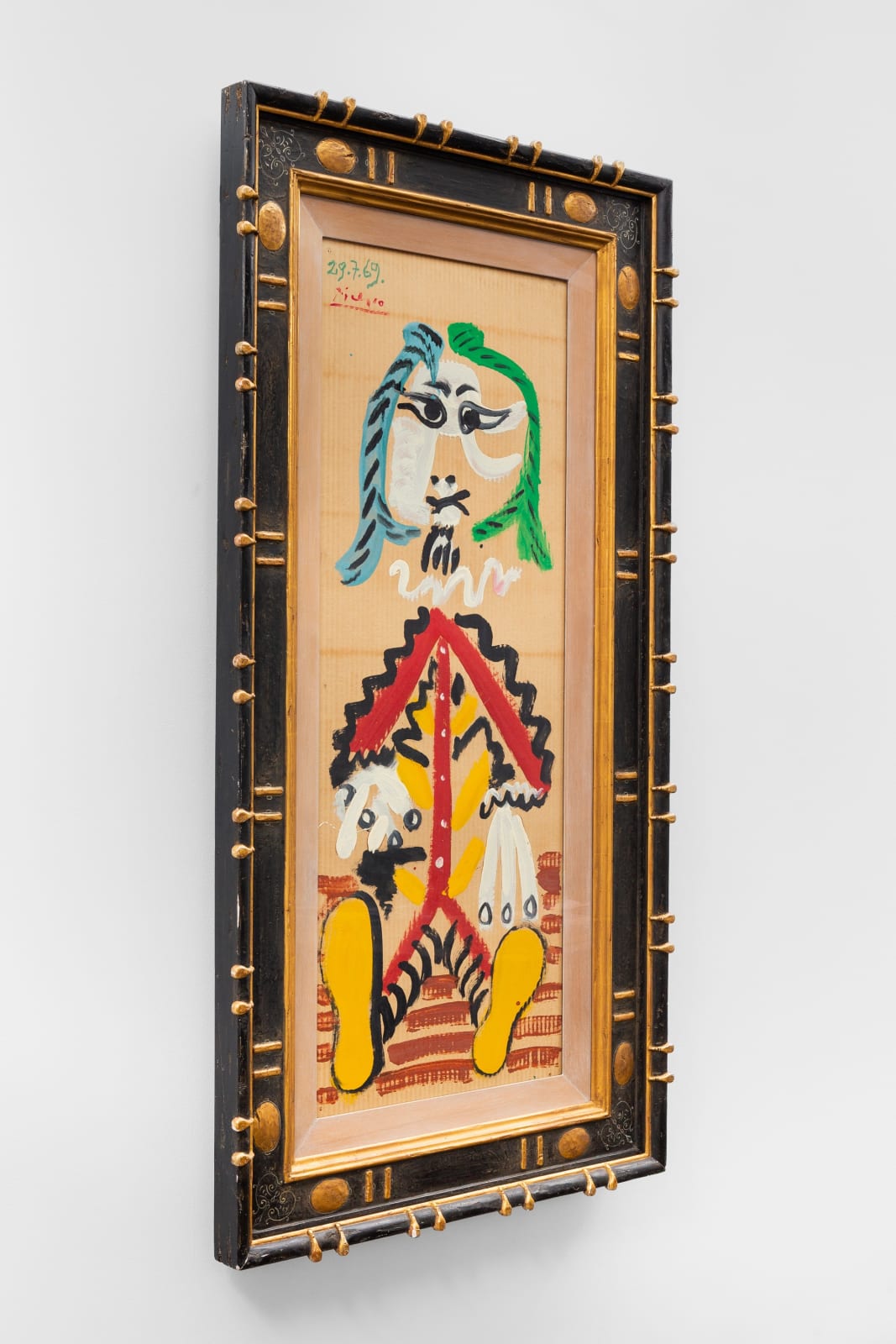

Pablo Picasso Spanish, 1881-1973

Homme Assis, 1969

Oil on cardboard laid down on canvas

128 x 50 cm. (50 3/8 x 19 3/4 in.)

Copyright The Artist

Homme Assis, executed by Pablo Picasso in 1969, stands as a vivid testament to the artist's undying creative vigour in the final chapter of his life. This painting, one of...

Homme Assis, executed by Pablo Picasso in 1969, stands as a vivid testament to the artist's undying creative vigour in the final chapter of his life. This painting, one of three completed on the same day, distills Picasso's introspective genius and playful irony through the lens of his archetypal mousquetaire, a figure emblematic of his late work. With his distinctive mirada Fuerte – or “strong gaze” – this seated swordsman exudes both humour and gravitas, the synthesis of a lifetime’s exploration into human complexity.

In his late 80s, Picasso found himself in a period of solitude at his home in Vallauris, where he rigorously made art with a relentless passion. Removed from the art world’s bustling capitals, he had only his wife, Jacqueline, as his close companion, and he journeyed inward, exploring his memories, his fears, and his enduring identity through his work. These later years were paradoxically some of Picasso's most prolific. After undergoing major surgery in 1966, he began revisiting literary and historical archetypes, notably inspired by Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. His fascination with the 17th-century cavalier – a symbol of the Siecle d’Or, or Golden Age – sparked a new genre in his oeuvre: the dashing, romanticised musketeer, an incarnation of both Spanish and French cultural legacies, invoking Velázquez’s noble hidalgo yet dressed in French attire.

By 1969, Picasso’s musketeer had become his primary persona, an audacious expression of his own enduring rebellion against age. Gone was the muscular fisherman of earlier self-portraits, supplanted by a figure who is equal parts grandiose and absurd. In Homme Assis, this nobleman with his upturned feet, exaggerated hands, and a somewhat bewildered expression embodies a duality that is comical yet profound. Far from a mere costume, the character speaks to Picasso's defiant spirit, a laugh in the face of mortality, while poking fun at the solemnity of age.

This anti-heroic vision reflects a broader commentary on human nature and war. As Dakin Hart observed, Picasso’s musketeers form “a kind of multinational, trans-historical hippie army engaged in a catalogue of alternatives to fighting.“ These musketeers, he posits, are driven not by the ”organised business of death“ but by a celebration of life – a timely statement during the late 1960s, as social and political turmoil worldwide pressed Picasso to express, in veiled allegory, his views on conflict and peace. Though dressed in anachronistic attire and cloaked in historical references, Homme Assis remains deeply resonant with the era’s anti-war sentiment, serving as a quiet protest and a tribute to resilience.

This painting was included in Picasso’s landmark exhibition Picasso: Oeuvres 1969-1970, which his longtime friend Yvonne Zervos organised at the Palais des Papes in Avignon in 1970. This significant show, featuring 165 paintings and 45 drawings, showcased his prolific output over a mere year and a half, asserting Picasso’s unmatched vitality and ingenuity even in his final years. In Homme Assis, Picasso presents us with a character that, like himself, is filled with contradictions – venerable yet absurd, commanding yet slightly comical. Through this figure, Picasso channels the weight of tradition and the joy of subversion, combining history and self-reflection into a uniquely engaging and deeply personal work.

In his late 80s, Picasso found himself in a period of solitude at his home in Vallauris, where he rigorously made art with a relentless passion. Removed from the art world’s bustling capitals, he had only his wife, Jacqueline, as his close companion, and he journeyed inward, exploring his memories, his fears, and his enduring identity through his work. These later years were paradoxically some of Picasso's most prolific. After undergoing major surgery in 1966, he began revisiting literary and historical archetypes, notably inspired by Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. His fascination with the 17th-century cavalier – a symbol of the Siecle d’Or, or Golden Age – sparked a new genre in his oeuvre: the dashing, romanticised musketeer, an incarnation of both Spanish and French cultural legacies, invoking Velázquez’s noble hidalgo yet dressed in French attire.

By 1969, Picasso’s musketeer had become his primary persona, an audacious expression of his own enduring rebellion against age. Gone was the muscular fisherman of earlier self-portraits, supplanted by a figure who is equal parts grandiose and absurd. In Homme Assis, this nobleman with his upturned feet, exaggerated hands, and a somewhat bewildered expression embodies a duality that is comical yet profound. Far from a mere costume, the character speaks to Picasso's defiant spirit, a laugh in the face of mortality, while poking fun at the solemnity of age.

This anti-heroic vision reflects a broader commentary on human nature and war. As Dakin Hart observed, Picasso’s musketeers form “a kind of multinational, trans-historical hippie army engaged in a catalogue of alternatives to fighting.“ These musketeers, he posits, are driven not by the ”organised business of death“ but by a celebration of life – a timely statement during the late 1960s, as social and political turmoil worldwide pressed Picasso to express, in veiled allegory, his views on conflict and peace. Though dressed in anachronistic attire and cloaked in historical references, Homme Assis remains deeply resonant with the era’s anti-war sentiment, serving as a quiet protest and a tribute to resilience.

This painting was included in Picasso’s landmark exhibition Picasso: Oeuvres 1969-1970, which his longtime friend Yvonne Zervos organised at the Palais des Papes in Avignon in 1970. This significant show, featuring 165 paintings and 45 drawings, showcased his prolific output over a mere year and a half, asserting Picasso’s unmatched vitality and ingenuity even in his final years. In Homme Assis, Picasso presents us with a character that, like himself, is filled with contradictions – venerable yet absurd, commanding yet slightly comical. Through this figure, Picasso channels the weight of tradition and the joy of subversion, combining history and self-reflection into a uniquely engaging and deeply personal work.