There’s often a reflexivity in your work – painting your studio, painting paint. It starts to become quite circular. Is that about storytelling?

I’m definitely a painter of everyday life. Everyday life is the most interesting thing to me. I like taking things that everybody sees – a thrift store, a friend on a couch, a cat and a dead pigeon – and then finding different ways of inventing within those frameworks. Having rules helps me do that. If I set limits, then the invention and storytelling can unfold within them, and the work feels more believable – to me and to the viewer – and allows me to tell little stories along the way.

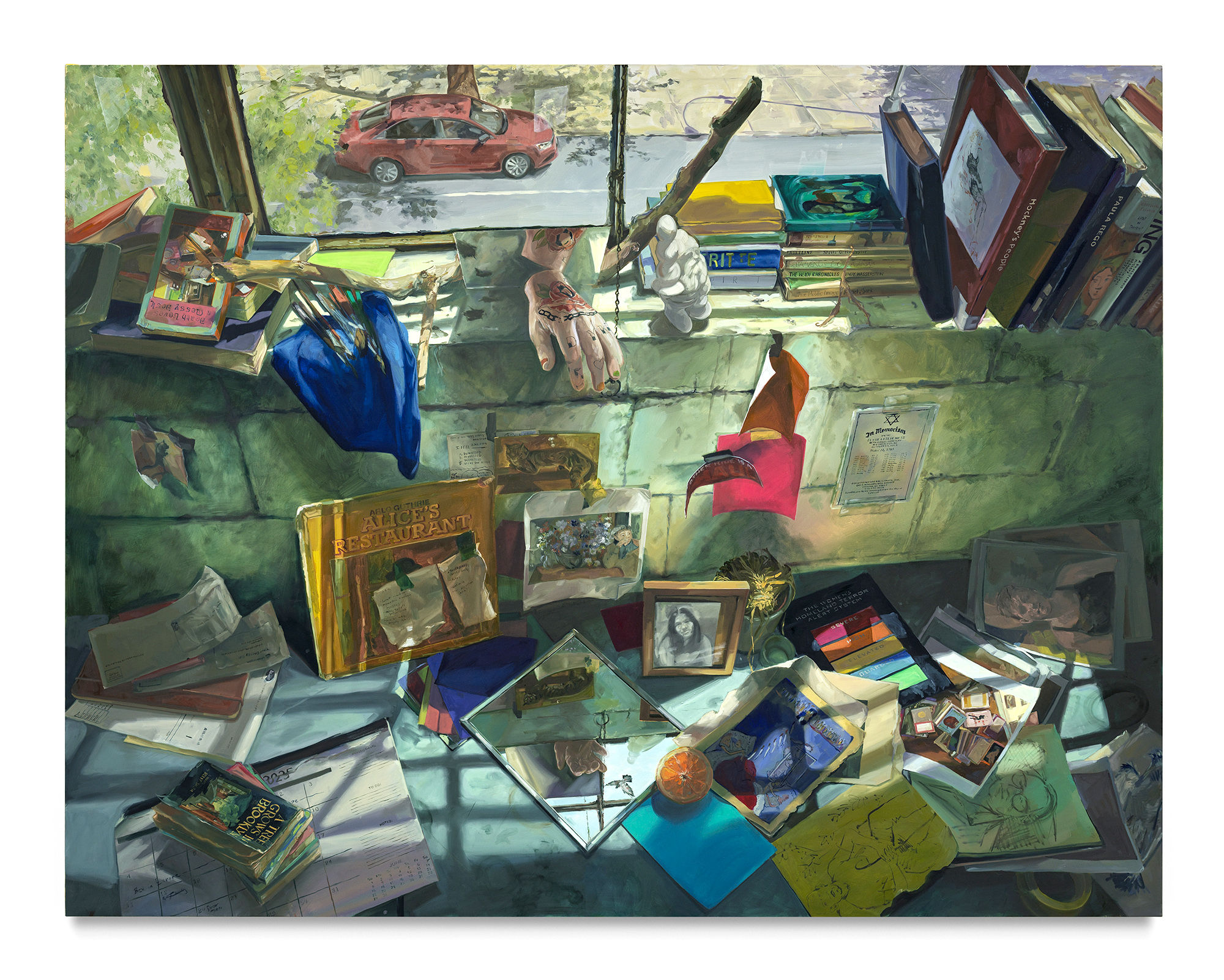

I love recreating something that exists in real life and noticing something new in the everyday. In my painting Altar, it’s my desk – but then I see a puddle I hadn’t noticed before. Suddenly there’s this challenge to paint a puddle, which is exciting!

That’s what I love about painting everyday life. Our eye is not as magical as we’d like – I can’t see everything that exists in front of me. But, if you look at something long enough, you work through the muck to find that puddle, or the edge of a table I hadn’t seen before, or in a photo of my mother, a glint in her eye that wasn’t visible to me half an hour earlier.

That circular quality of painting what’s around me, and then really sitting with it, is what keeps me hooked. The more you look, the more everyday life keeps giving back, if you stay with it long enough.

Altar, 2025

Oil on linen

177.8 x 228.6 cm. (70 x 90 in.)

Can you give me an example of one of those 'little stories' you tell along the way?

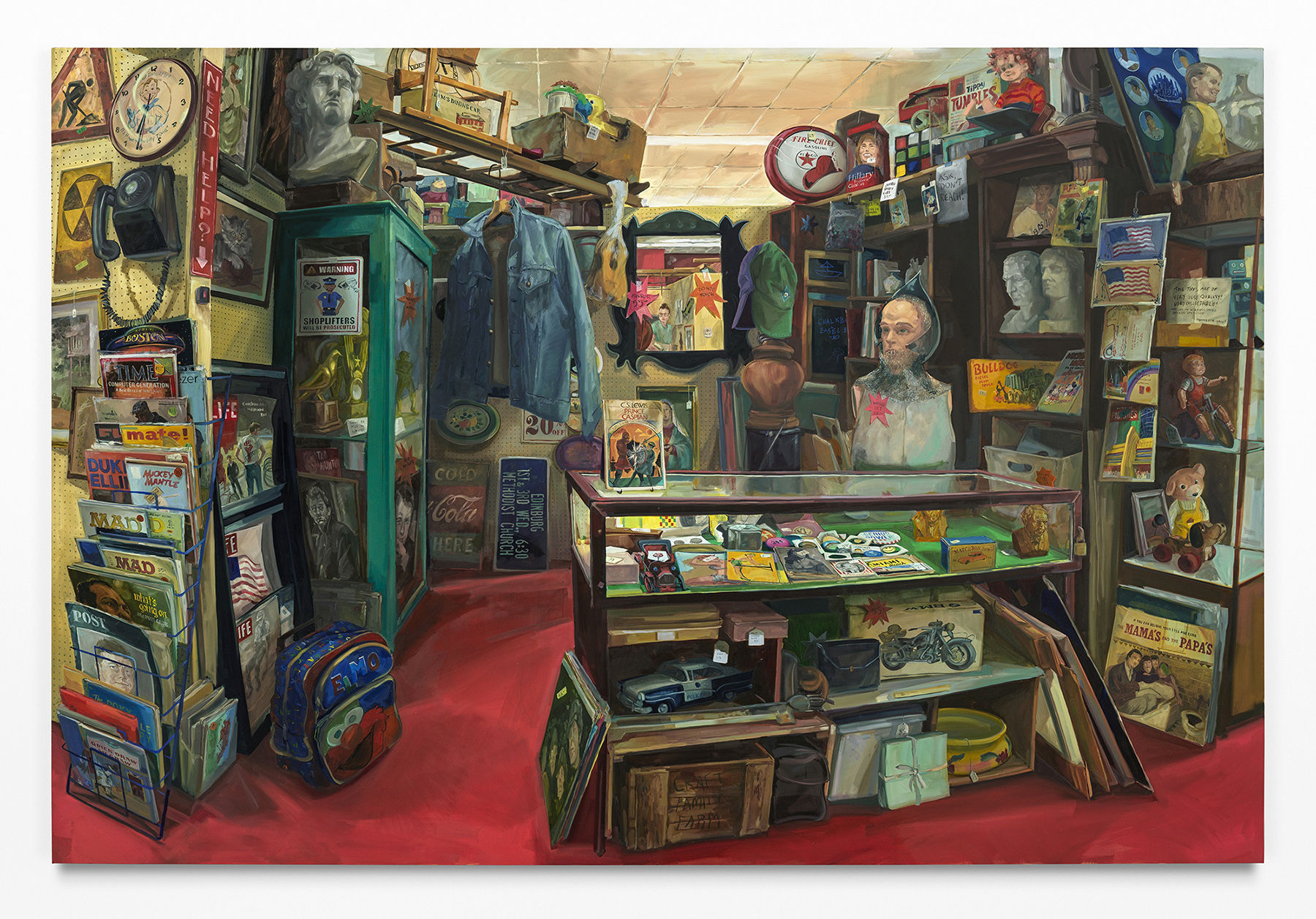

I visited a thrift shop in Staten Island called Remembering Yesteryears that inspired me to paint Other people's things. It’s full of a million little stories. I think of the painting as a group portrait.

I used to think about these ‘stuff’ paintings as being about “we are what we keep.” But in the past year, after experiencing grief, I started thinking about objects in terms of “we are what we leave behind” too.

Walking through that thrift store, I’d see a basket of dolls or a pile of old Time magazines and think this was someone’s whole life. I took those real, past lives and then editorialised a little – inserting some of my own things too. I collect Life magazines, so I placed some of mine among the thrift store objects. It became a mixture of documentation and my own storytelling.

Other people's things, 2025

Oil on linen

203.2 x 304.8 cm. (80 x 120 in.)

Would you say you’re ultimately a painter of people? Are objects only there to imply or infer people?

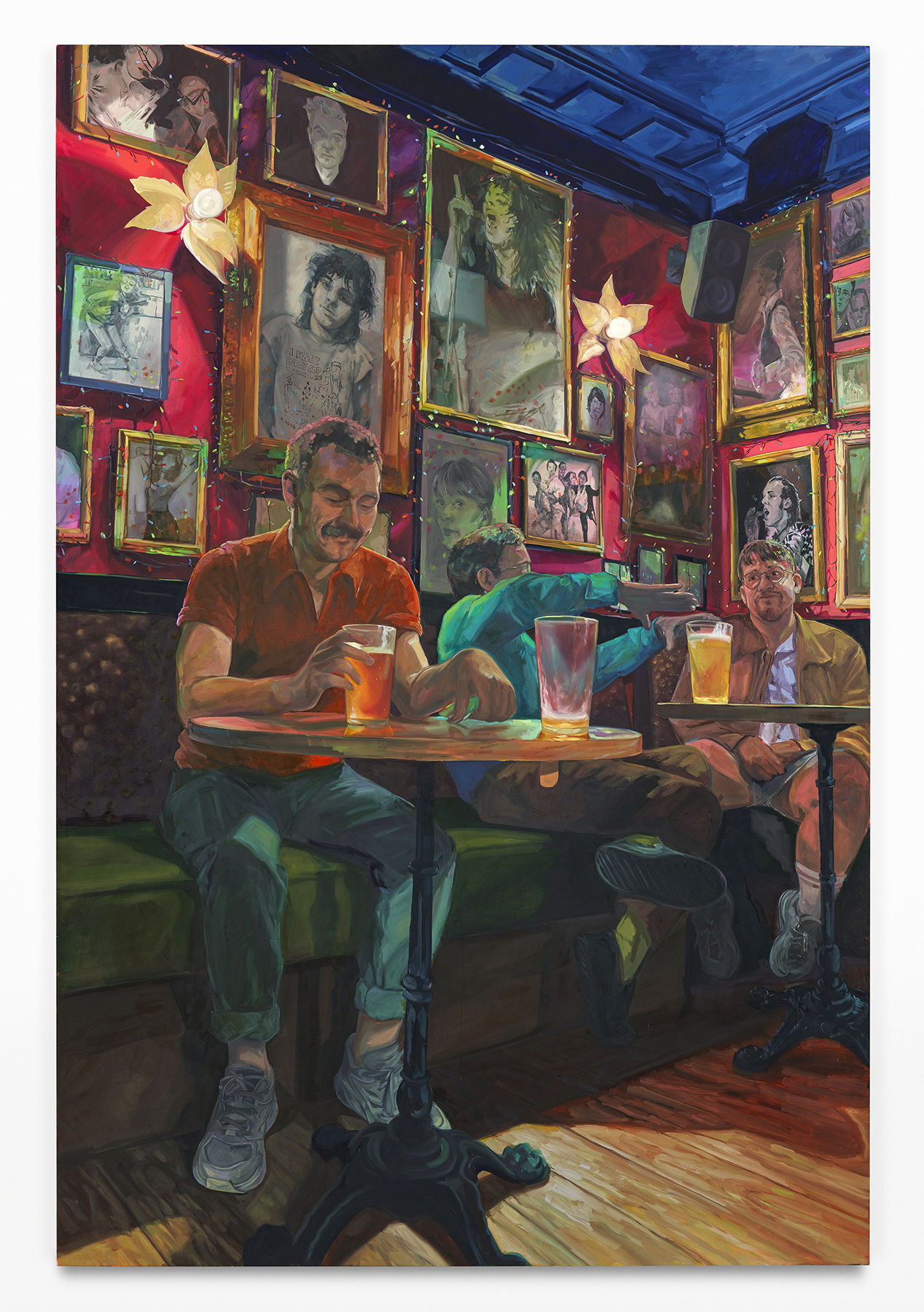

I’m definitely a portrait painter in the broadest sense. Anything I paint feels like a portrait. Not always of one person – sometimes it’s a group portrait, or even a portrait of a space that holds people, living or gone.

Take my gay bar paintings – they’re portraits of people, of course, but also of the space itself, the community it holds, the ghosts of people who’ve been there before. In Retro Bar for example, you see three actual people, but also Bon Jovi, Cyndi Lauper, David Bowie, all appearing on posters behind them. The space itself becomes part of the portrait.

Retro Bar, 2025

Oil on linen

228.6 x 152.4 cm. (90 x 60 in.)

You’ve made a painting called Painter’s chair, which connects directly to Freud.

Yes, Painters chair is an homage to a hero. I was very lucky growing up to go to the small art school in my town called Acorn Gallery School of Art. When I was six, I was taught that Freud was God. I grew up revering Freud – I knew who he was before Picasso or Monet. When he died, my art school toasted him with grape juice.

Earlier this year, I had the chance to visit his studio in London, thanks to the gallery, and I cried as soon as I stepped into the space. It felt like meeting a place I’d been told about, that I’d read about, my whole life.

Painter’s Chair came out of that experience. It’s not an imitation, but a thank-you to him. I used my own language, in my own way, to acknowledge what I’ve learnt. I wasn’t interested in reproducing his paint splatters exactly, rather, inserting my own. It’s more like a student showing what they’ve absorbed and transforming it through their own language.

Painter’s chair, 2025

Oil on linen

101.6 x 76.2 cm. (40 x 30 in.)

How do you see yourself as different from Freud?

Freud treated a face as an object to inspect. He was obsessed with precision – every mole, every wrinkle, exactly where it was. I’m less interested in strict observation and more in invention. If shifting a mole a little to the left makes the light work better for the story, I’ll move it. If Kelley’s hat works better orange than its real colour, I’ll paint it orange. I follow rules, but I bend them for the world I’m trying to depict.

I don’t want to be Freud. I want to be me. I’m grateful to him, but invention is central to how I paint.