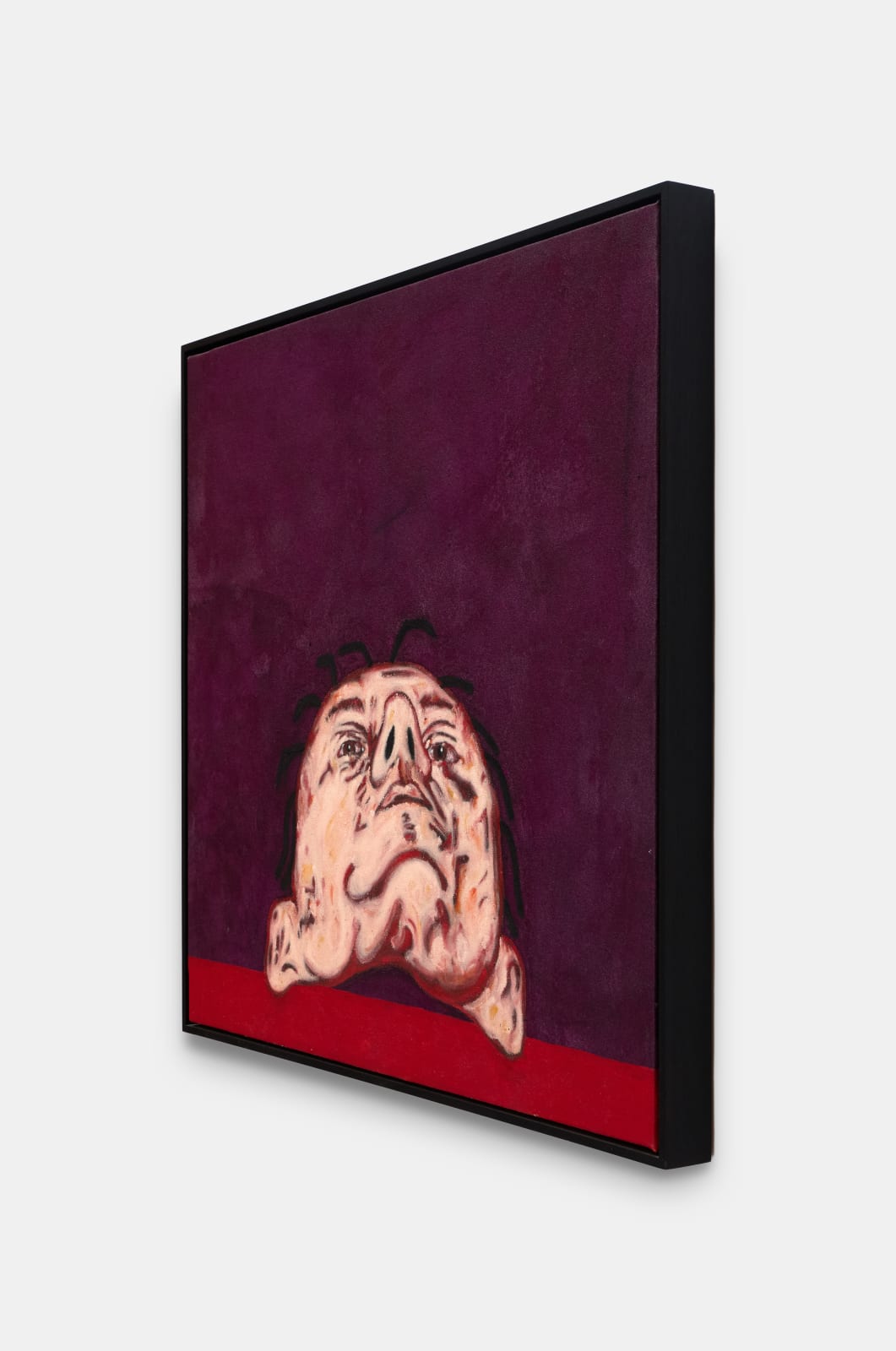

Tony Bevan British, b. 1951

Head Horizon (PC967), 1996

Acrylic and charcoal on canvas

88.9 x 95.3 cm. (35 x 37 1/2 in.)

Copyright The Artist

Further images

Since the early 1990s, the human head has been Tony Bevan’s most obsessive subject, one he has relentlessly revisited and reinvented. Bevan frequently isolates and detaches the head from the...

Since the early 1990s, the human head has been Tony Bevan’s most obsessive subject, one he has relentlessly revisited and reinvented. Bevan frequently isolates and detaches the head from the body, so it hovers within the picture plane, often monumental in scale. Rendered in bold, lacerated charcoal outlines, it appears as though carved directly into the canvas. These bold linear gestures not only map the surface of the face but seem to reveal its inner architecture, as if the surface of the skin has been peeled back to expose the muscle and veins. The effect is gnarly and raw, charting an architecture of emotion made manifest through line and texture.

His heads are seldom presented from conventional viewpoints. Bevan often adopts a contre plongée perspective, depicting the head as if seen from below. Flared nostrils thrust upward into view, lending the head the solidity of a boulder or mountain. This skewed angle heightens an unsettling potency, positioning the spectator beneath a colossal form that is simultaneously intimate and alien.

Bevan’s process is austere, tactile and physical. He grinds his own pigments, suspending them in a clear, glossy acrylic medium more akin to sizing than a traditional opaque primer. This reveals the natural linen weave and emphasises the canvas’s raw material. Working on the studio floor, he applies charcoal drawings to the still-wet ground so that his marks sink into the canvas fibres. He then deposits raw pigment and paint with truncated brushes and his own hands. The rapid drying of acrylic forces a dynamic working style; clumps of pigment adhere to the surface, areas of canvas remain bare, and the resulting matt, textured finish discloses the labour of creation.

Many of the heads are essentially self portraits as Bevan uses his own head as model. But rather than pursuing likeness, Bevan maps psychological conditions through his own visage and uses the head as a vessel for complex emotional states. The head thus functions as a psychic container – its scarred, abstracted surfaces encoding layers of character and mood.

Where conventional portraiture might capture appearance, Bevan’s heads transcend it. His artistic vocabulary evokes Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s “character heads,” transmuted into a contemporary idiom of deformation and structural simplification. The head becomes a liminal space – architecture and flesh interlacing in forms that hover on the edge of abstraction while remaining unmistakably human in presence.

In sum, within Bevan’s oeuvre the human head is not a motif but an existential locus. It is through these disquieting, monumental heads that Bevan engages with the depths of human experience – visceral, vulnerable and unescapably intense.

His heads are seldom presented from conventional viewpoints. Bevan often adopts a contre plongée perspective, depicting the head as if seen from below. Flared nostrils thrust upward into view, lending the head the solidity of a boulder or mountain. This skewed angle heightens an unsettling potency, positioning the spectator beneath a colossal form that is simultaneously intimate and alien.

Bevan’s process is austere, tactile and physical. He grinds his own pigments, suspending them in a clear, glossy acrylic medium more akin to sizing than a traditional opaque primer. This reveals the natural linen weave and emphasises the canvas’s raw material. Working on the studio floor, he applies charcoal drawings to the still-wet ground so that his marks sink into the canvas fibres. He then deposits raw pigment and paint with truncated brushes and his own hands. The rapid drying of acrylic forces a dynamic working style; clumps of pigment adhere to the surface, areas of canvas remain bare, and the resulting matt, textured finish discloses the labour of creation.

Many of the heads are essentially self portraits as Bevan uses his own head as model. But rather than pursuing likeness, Bevan maps psychological conditions through his own visage and uses the head as a vessel for complex emotional states. The head thus functions as a psychic container – its scarred, abstracted surfaces encoding layers of character and mood.

Where conventional portraiture might capture appearance, Bevan’s heads transcend it. His artistic vocabulary evokes Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s “character heads,” transmuted into a contemporary idiom of deformation and structural simplification. The head becomes a liminal space – architecture and flesh interlacing in forms that hover on the edge of abstraction while remaining unmistakably human in presence.

In sum, within Bevan’s oeuvre the human head is not a motif but an existential locus. It is through these disquieting, monumental heads that Bevan engages with the depths of human experience – visceral, vulnerable and unescapably intense.